How many unweavings does it take to bring a new reality into being?

An essay on weaving, unweaving, and sustaining relational bonds in times of collapse

Preface

I wrote this text during a gathering with artists, activists, and storytellers from the Arab world.

Amid conversations, performances, and silences, I was traversed by the pains of Gaza, the dignity of resisting voices, and my own impotence in the face of what I cannot change.

This is not a text about war. Nor about geopolitics.

It is a text that was born as I tried to sustain my presence before a world that unravels—without completely unraveling with it.

It is about weaving, unweaving, and waiting.

It is about learning to lose... without losing the listening.

Perhaps it is also a small offering, among the ruins, for those who still believe that words, even fragile ones, can sustain bonds.

Weaving, Unweaving, and Waiting

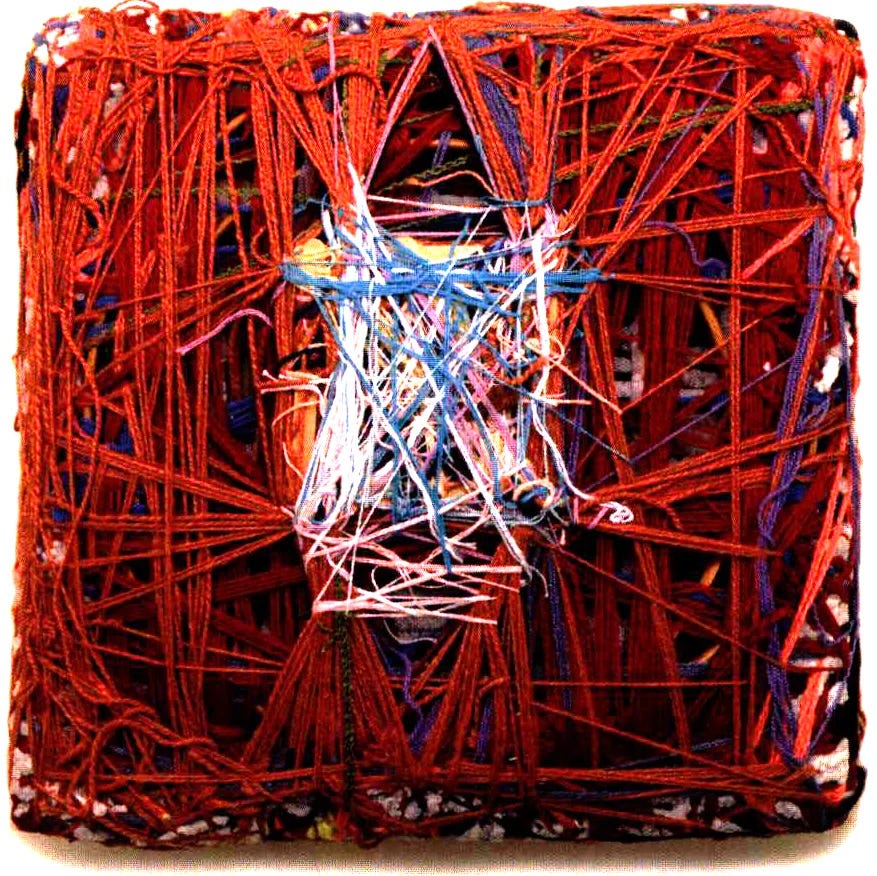

One of the images I like to use to explain the work of building narrative power is the image of weaving.

The narrative is the tapestry—the stories, the threads. Each thread, with its own color, length, and texture, is patiently interwoven until a pattern, an image, emerges. All of this within an infrastructure that supports the entire work: the loom.

At first glance, explaining narrative work with this metaphor is simple.

But it is precisely this apparent simplicity that unsettles me.

Whose hand interlaces the threads? Who chooses the pattern, the print?

And if the loom—that structure that supports everything—already carries invisible limits?

Who built it? Which voices does it favor? What patterns does it allow us to imagine?

And which others, perhaps, does it not even recognize as possible?

I think here of Indy Johar’s provocation:

"Our systems were built to reinforce a particular story—that the world is composed of parts, and progress means mastering those parts. But we are not parts. We are not discrete. We are relational fields, co-constituted across space and time. Every action ripples. Every decision implicates."

If we take this perspective seriously, then the loom is not just a neutral tool.

It is also a story—one that can limit our collective imagination if left uninterrogated.

For me, that's where the mystery lives.

If the loom is also a story, then maybe the real narrative work is not just about weaving threads, but noticing the loom itself.

Some structures shape us before we even begin to speak.

Some frames are so old, so normalized, that we no longer see them.

And yet, it is from them that we weave.

How many times do we tell stories believing we are creating change, when in fact we are only reinforcing the same patterns, repeating the same design with new threads?

Perhaps building narrative power today requires more than storytelling skill.

Perhaps it demands a more subtle—and radical—gesture:

Listening to what remains unsaid.

Noticing which threads were discarded.

Which textures were denied.

Which colors were never allowed in.

And perhaps… imagining another loom.

Or even asking:

What if it’s no longer time to weave tapestries?

What if it’s time to unweave—to undo—to let the threads breathe for a while,

until another form of pattern, still unnamed, begins to emerge?

Unweaving is not going backward.

It is stepping onto a different path— one that begins with listening to the places where the weave became too tight,

where the design repeated itself without question,

where the thread lost its breath.

Unweaving demands awareness. Sometimes more than weaving.

Because weaving gives us direction.

Unweaving returns us to the question.

Weaving builds patterns.

Unweaving exposes them, softens them, makes them porous to the unexpected.

Unweaving is a practice of presence—

with what was, with what is, and with what might never be.

It is a work of mourning and release.

An act of radical love for something not yet born— something that can only emerge if space is made.

Maybe this is the most difficult narrative power of our time:

The power to stop weaving.

To recognize the patterns we cling to.

And to trust that, by unweaving with care, something more alive can take form.

And what if—within this act of unweaving—imagination found a deeper place to dwell?

We often see imagination as the force that propels the new, shapes futures, and designs forms.

But there is another kind of imagination—quieter, slower— the one that lives in the act of undoing.

The imagination that sustains unweaving does not project; it listens.

It does not deliver answers; it holds the question.

It trusts that even without a pattern, even without a design, even in a tangle of loose threads— life is pulsing, waiting for another rhythm, another texture, another dance.

This imagination does not want to form an image.

It wants to make space.

And in the end—or maybe the beginning of something else—

I return to a phrase I’ve carried with me for almost thirty years,

spoken by a friend in one of those moments when time seems to pause:

“In life, we have to learn two things: to lose, and to wait.”

Losing is unweaving.

Waiting is trusting the empty space between threads.

Waiting: not by guaranteeing, not by forcing, not by rushing— but by sustaining the field, so something can still inform, still inform, and perhaps take shape.

Losing and waiting are not passive gestures.

They are gestures of relational faith.

They are the invisible weave of every process of deep reimagination.

And the act of waiting—not for a happy ending, but for another rhythm of existence—

might only reveal itself to those who accept losing without losing themselves.

Perhaps it will not be to us that this new rhythm is revealed.

Perhaps it will be other hands, other eyes, other generations who will one day witness its design— delicate and resilient— emerging between the traces we leave

when we learn to lose and to wait.

.